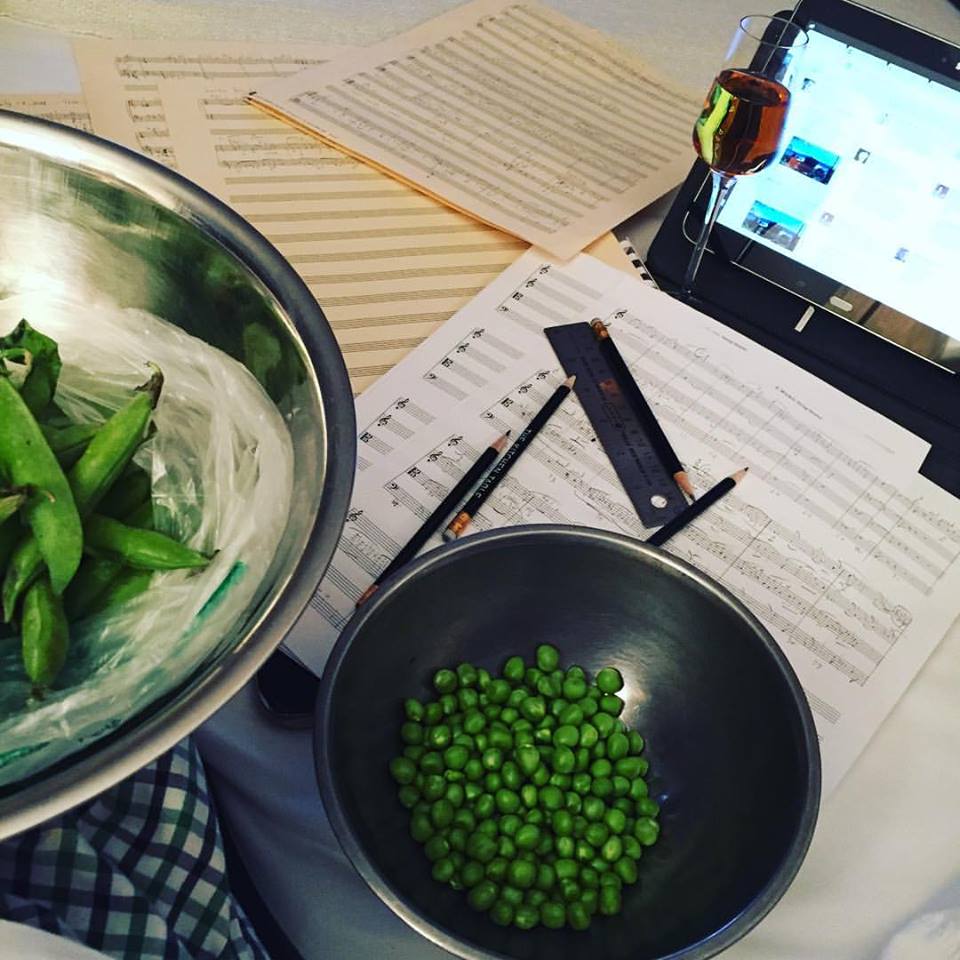

Hi. My name is Ed. And I’m a 5 to 9 composer. In other words, I also have a day job.

It’s been 25 years since my last stint as a full-time composer. That was the year I received my master’s degree from the Mannes College of Music in New York. For most of the interim, I’ve been composing during the hours not occupied by my various corporate jobs, most of them in the legendarily glamorous world of advertising.

Actually, now that I think about it, I’ve never truly been a full-time composer, even during school. I’ve always had to support myself through means other than music, including paying my own way through undergrad and graduate schools. Since I lack sufficient instrumental ability to support myself as a performer or the temperament for academia, making a salary in various office capacities has provided several advantages to maintaining a life as an artist (which I’ll elaborate on in the upcoming posts), both during my school years and since—even if it is more time consuming than I’d ideally like.

Day jobbing as an artist has been the subject of substantial digital press across all genres. And we in the concert music world have many illustrious predecessors who supported themselves through additional careers. Hector Berlioz and Virgil Thomson both spent much of their lives as critics. Alexander Borodin worked as a chemist. Morton Feldman ran his uncle’s garment factory for years. Most famously, Charles Ives spent most of his life as an insurance broker while turning out some of the most revolutionary works of the 20th century.

While I’ve never denied my situation, until now I have preferred to keep quiet about it. I let myself be intimidated by a long-standing and short-sighted mindset within the greater concert music world that if you are not a “full-time” composer (I include composers with academic positions in that definition)—and preferably struggling financially—you are somehow less serious, less committed, and less worthy. For too long I succumbed to this ideology. If I wasn’t making at least the majority of my income from music or composing, I didn’t deserve to call myself a composer.

So why take up the banner about it now?

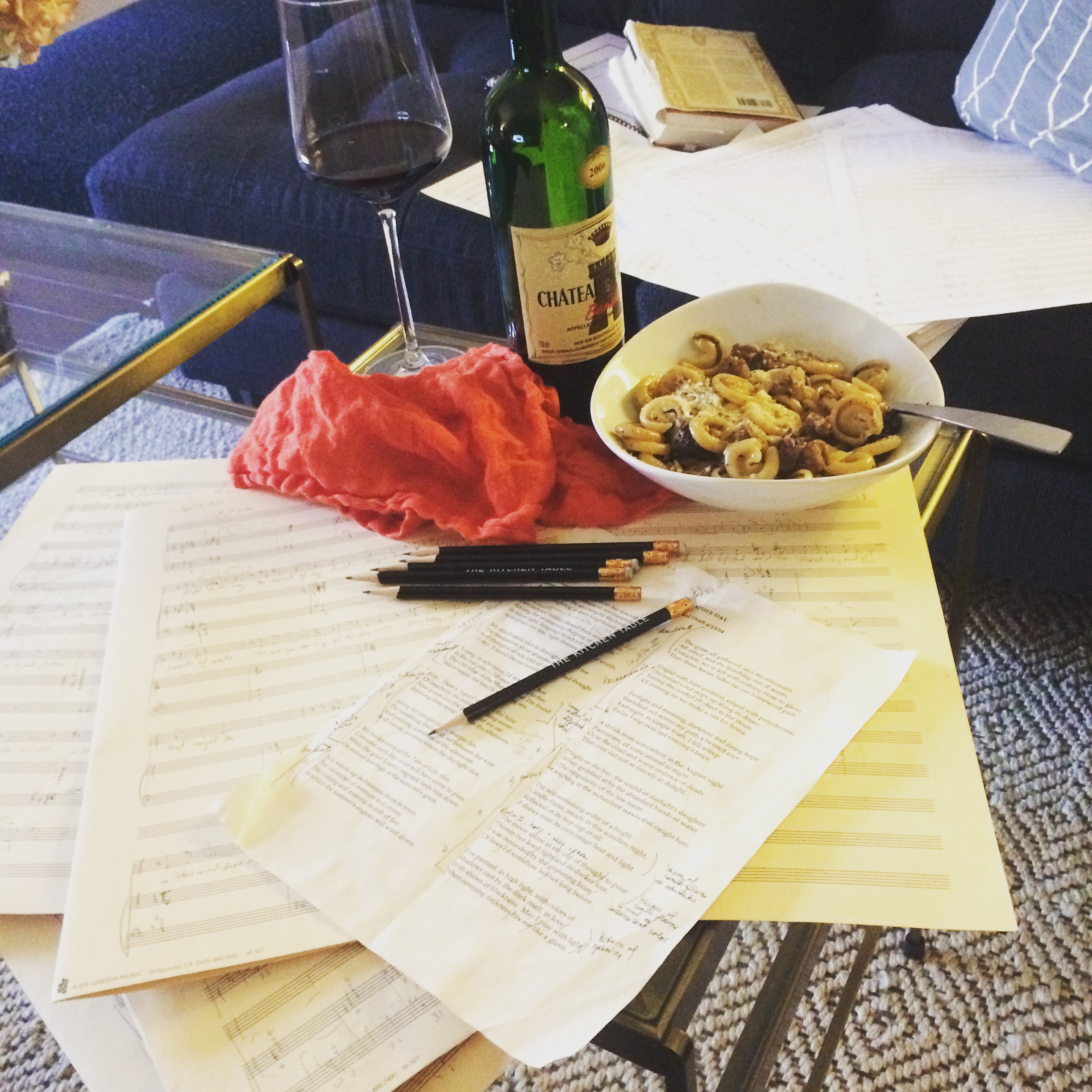

A variety of factors led me in 2011 to seriously re-enter and re-engage with the worlds of both concert music (as a composer) and theater music (as an orchestrator and arranger). And despite the many extraordinary developments in the musical world, I found myself still confronted with this same attitude. So not only has it become necessary to embrace my circumstances with self-respect, it’s become a mission of empowerment.

I’m out to dispel this derogatory mindset, not only for my own sake but for the current generation of artists entering the field. There are thousands of people in the world aspiring to be composers or musicians, of whatever genre in whatever field. Not making all or even most of your living directly in your vocation shouldn’t prohibit you from identifying yourself in that vocation or make you feel less worthy.

Increasingly when I’m introduced in public or speak at events, I find myself approached by younger composers and performers—in both my concert music and theatrical lives—wondering what their options are to make a financially reliable living while still pursuing their artistic goals. Some of them quail at the amount of competition in every facet of the music world, others at the prospect of years of financial uncertainty.

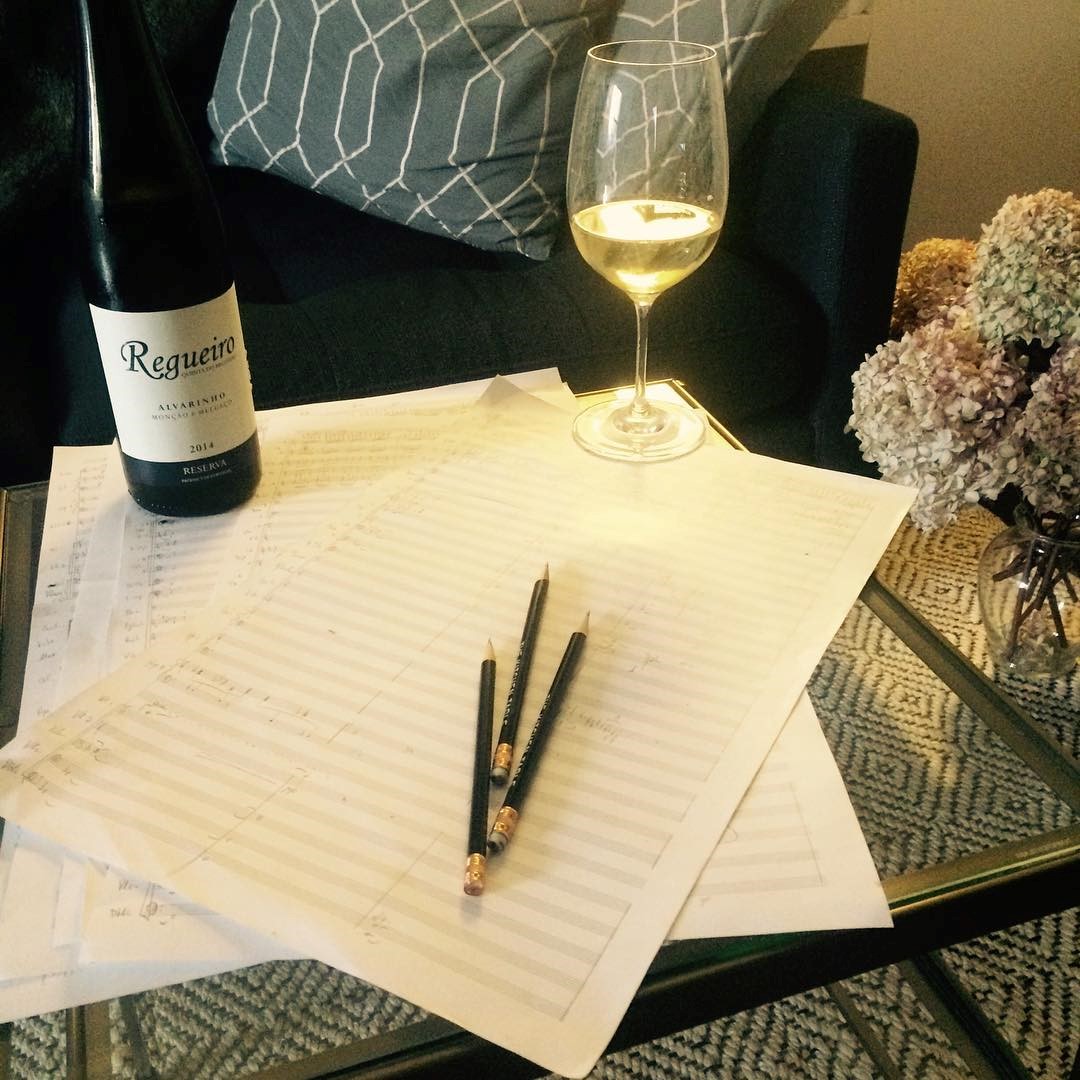

So on their behalf and my own, I am here to proudly proclaim: yes, I am a composer with a day job, and it’s a viable way of managing your life as an artist—full time or long term or otherwise. And to dispel the shame and opprobrium still cast on this pathway, I’m publicly adding my voice to the coterie of double-fisting artists. Our method may not be the most creatively ideal or produce the largest body of work—issues I’ll explore in upcoming posts—but it could arguably improve creative output because of the financial security and the overall life stability it provides.

An omnivore of the fine and performing arts, Ed Windels spent his youth trying his hand at many of them before devoting his studies to classical music. After a year at the Juilliard School, he completed his studies at the Mannes College of Music, earning both bachelors and master’s degrees in composition in just three years. Ed has mostly pursued projects and built his catalogue in private, a course that has continued to bear remarkable fruit since a showcase concert of his works by NewMusicNewYork in February 2010. Recent commissions include a song cycle for Bargemusic’s Here and Now series and a piano solo piece for his alma mater. Currently in the works are his first string quartet, a large-scale piece for tenor and orchestra based on John Hollander’s Summer Day, and a version of Richard Strauss’s Elektra for reduced orchestra. Additionally his admiration for and experience with the musical theater has resulted in a burgeoning additional career as an orchestrator and arranger.