Arts entrepreneurship has received a lot of attention in recent years. Programs have popped up at numerous institutions, and the discourse of entrepreneurship is a hot topic in the circles of contemporary music. Building on my first post in this series, I’d like to examine some of the underlying assumptions and root causes of the entrepreneurship phenomena and its larger implications for composers within society.

As a student, I was told it was nearly impossible to make a living just as a composer. One then has a variety of other options: work in the very competitive commercial sphere of film, video, games, and jingles; teach (either privately or institutionally); work some other job, utilizing any number of skills, that then (hopefully) allows you to support your music and vision; or a hodgepodge of the above. All this is well and good, except what happens when composers are not so interested in being arts administrators, not so adept at social media or fundraising, not so easily assimilated in commercial industry? What of the composers who are perhaps not so inclined as performers, whose strengths do not fit the entrepreneur?

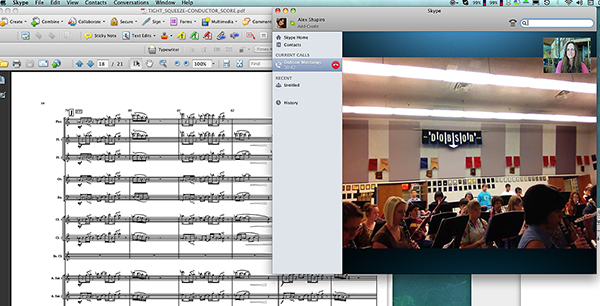

This is the ubiquitous scenario that every composer faces. Being a composer of any age today requires a lot of work, dedication, thought and inspiration. A composer also faces a variety of post-composing challenges. Composing on its own is a full-time job. Yet after you complete a piece, you now often have to see to the organization and performance of that piece yourself—finding adequate performers and venues, raising money to support the event, and managing effective promotion. You are told as a student that no one else will do it for you. However, there are some composers that still get large-scale commissions, performances, and credits in movies, so you know somewhere, someplace there are people working as composers and there is money to support them. It’s clear that these are dwindling exceptions to the norm, however, and that there is just not enough money to go around. Therefore, we are obliged to conjure both a cultural and economic space for our art after creating it. This can be compared to an architect who, upon completing delicate plans and specifications, has to build it himself, including footing the bill for materials, labor, and space to implement his vision.

In the past, composers were often the pet geniuses of wealthy patrons—royalty and titans of industry who took care of them and facilitated their career. An argument could be made that being a composer has never been a “real” job but a way of life—what Robert Henri called the “art spirit.” In fact, Henri wrote that he was interested in art as “a means of living a life; not as a means of making a living.” Professor Linda Essig is an outspoken advocate of arts entrepreneurship, and highlights the role of middle class artists, who are neither impoverished nor made wealthy from their art: “[Call] it arts entrepreneurship or call it artist self-management, it is part of the work-life of the artist in the US. It is these artists, the artists in the middle, who can serve the social good, create excellent work, and critique this system in a meaningful way.”

The broader economic realities of the widening wealth gap along with the systematic destruction of the middle class makes Essig’s statement to potential students a confusing mandate. My question to Linda Essig is this: how can artists serve the social good, create excellent work, and critique the system when it is the system which is actively eroding the social good and preventing them from accomplishing excellent work?

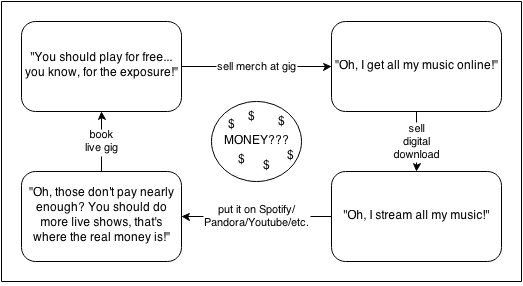

The result is not meaningful creative engagement but a scramble for survival—a blurring of vision and base opportunism. Composer Nicholas Chase cites the almighty dollar on his blog:

To paint the reality of this in dollar amounts, the 2012 National Endowment of the Arts report “How Arts Are Funded” revealed that the national budget of arts funding in the United States was $0.47 per-capita—compared to the next lowest per-capita funding of $2.98 in New Zealand. The remaining of English speaking countries surveyed revealed a shocking gap, leaping exponentially to $5.19 per capita in Canada and as high as $17.80 per capita in Wales, UK. However, the bleak picture the figures above give us isn’t merely financial or economic: it reveals the lack of incentive for artists to pursue careers in the arts, and implies the low range of pay administrators will take to foster Culture-Building…You begin to see how the question of issues is not merely mechanical or financial, but becomes a deeply social issue.

I recently had lunch with a friend and her boss, a man in his early sixties. We had a wonderful discussion about science, art, and consciousness. He was very interested in my music. I told him he could listen to my music for free by streaming it online. He insisted that he pay for it, adding that “it would help me if you gave me a price.” This was a surreal situation and I was taken aback, unprepared. I have not developed my website to include iTunes-style purchase and download capabilities, nor have I attained the support of record labels or ensembles that subsidize and distribute recordings. Why have I not developed my website? Mostly because I have been too busy honing my craft and composing. I value the quality and integrity of my work over selling it. I couldn’t argue with this patron who was sincerely interested in my music, but his appreciation was precluded by a deep ethic of transaction—that we must fix a value to a rather subjective non-fixed entity.

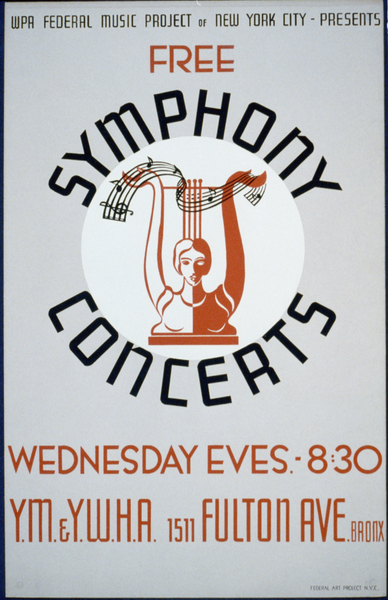

Poster for New York City Federal Music Project presentation of free symphony concerts at the Y.M. & Y.W.H.A.

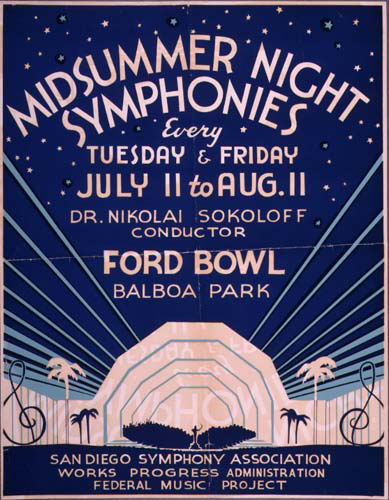

The ongoing discussions regarding the potentially unstable economics of music might do well to consider the ethic of the commons. Just as the air, land, water, and sunshine that sustains human beings is a common right and owned by everyone, so is the intellectual and creative common of society. Implicit within this paradigm, however, is a communal reciprocal relationship. Artists and musicians would create and offer their music and labor for free “consumption,” but consumers would then pay into a system that supports these artists and encourages more creative innovation and cultural enrichment. Our government could easily create such a system. The WPA Federal Music, Theater, and Writers projects during the Great Depression were a step in the right direction, as they employed thousands of artists, composers, and musicians. These projects were scuttled as the nation’s resources and energies were directed into another enterprise—war—and instead of creating art, people made bombs, and vast corporations were built to destroy cities and then build them again, making lots of money in the process.

Nicholas Chase further argues in a comment on NewMusicBox that “through a kind of social attrition, the perceived low-value of what I do has necessitated that I become an entrepreneur…which means I am playing dual, triple, quadruple roles in my field. I am the composer, often the commissioner, the producer, recently the performer…the issue we are facing today is the effectiveness of that model as it requires more and more and more attention from us as artists. It seems that the idea has become a convenient scapegoat for the handlers of Culture in the greater United States.”

If the fruits of our creative labor—our music, ideas, energies—are not considered valuable in the parameters of our society—if composing and performing music is not a worthy trade for food, shelter, and healthcare—then we must change our values as artists and either conform to the parameters and values of society or we must change the parameters and values of society. We will not solve these fundamental issues by encouraging artists to conform to the external pressures of society. Entrepreneurship, in this case, can be used as a valuable tool to redesign the social relationship of musicians and society—to encourage a complete re-evaluation.

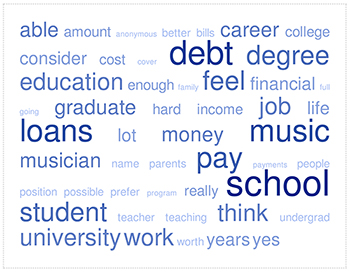

No matter how one slices it, for me these arguments and experiences point to one singular fact: we must alter our consciousness—that is, seek to live out alternative values to what is predominant in our society every day. This could be by collectively refusing to pay the impossible debt imposed upon young creatives, who continually work and create for the benefit of society with no monetary compensation. This could be by organizing more composer groups or empowering the many national and regional groups to engage in political and economic activism, demanding from our government the resources necessary to strengthen communities through artistic vision. This could be done by further developing alternative ways of funding such as BELTA or The Impresario Society, which seek to create new means of supporting artists and converting the wealth of society into meaningful creativity. This could be by posting more and more articles to incite more discussions that penetrate down to the true roots of our frustrations and injustices, rather than just treating their symptoms. This consciousness shift is the first creative moment, the precedent for the revolutionary act. One commenter describes this change of consciousness as an acceptance of truth:

Joseph Campbell during his talks with Bill Moyers was asked about shamans. Moyers wanted to know if shamans still exist and Campbell answered that modern shamans are our artists. During the moment of true creation, a possibility presents itself that can allow a shift or change in consciousness…The more of us that experience that insight, the more the possibility of a shift. A paradigm shift is possible but only when enough of us stop thinking for a moment, to be totally aware and allow Truth to enter…we have then entered the realm of the shaman/artist. This is the creative moment.